Quick facts

Common name - Potato blight, late blight

Scientific name - Phytophthora infestans

Plants affected - Potatoes

Main symptoms - Brown & rotting, shrivelled leaves. Decay of tubers

Caused by - Fungus-like (Oomycete) organism

Timing - Early summer onwards

What is potato blight?

Potato blight (also known as late blight) is a disease caused by a fungus-like (Oomycete) organism (Phytophthora infestans) that spreads rapidly through the foliage and tubers of potatoes in warm, wet weather, causing collapse and decay.

It is the most serious and damaging disease of potatoes and can also affect tomatoes (on which it is known as tomato blight) and some ornamental relatives of these two crops. Cases have been recorded on ornamental Solanum species (e.g. S. laciniatum), and very occasionally also on Petunia.

What is early blight of potatoes?

Early blight is a different disease that is found widely in North America, and is commonly reported on the internet. This fungal disease of potatoes is caused by Alternaria solani and A. alternata. It is not a common problem in British gardens, but can be confused with the symptoms caused by the much more common magnesium deficiency.

Symptoms

You may see the following symptoms in potato plants with late blight:

- The initial symptom of blight is a rapidly spreading, watery rot of the leaves, which soon collapse, shrivel and turn brown. During suitable conditions when the pathogen is actively spreading through the leaf tissues, the edges of the lesions may appear light green, and a fine white 'fungal' growth may be seen on the underside of the leaves

- Brown lesions may develop on the stems

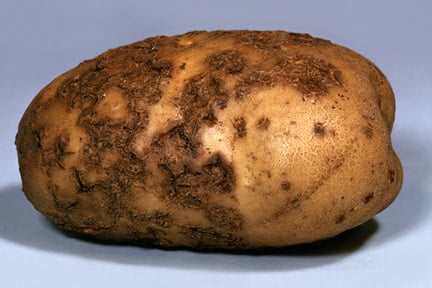

- If allowed to spread unchecked, the disease will reach the tubers. Affected tubers have a reddish-brown decay below the skin, firm at first but often soon developing into a soft rot as the blighted tissues are subsequently invaded by bacteria. Light attacks of blight may not be visible on the tubers, but many infected tubers will rot in store. Whilst the blight pathogen itself doesn’t spread much in store, the secondary bacterial rotting can spread to affect a large percentage of the tubers

Control

Non-chemical control

- Infected material should be deeplyburied (below the depth of cultivation), consigned to the local council collection or burned, rather than composted (see 'Biology' section, below)

- Earthing up potatoes well provides some protection to the tubers from blight spores washed down into the soil from lesions on the leaves or stems

- Early-harvested potatoes (e.g. first-early cultivars) are more likely to escape infection, as levels of the disease tend to increase as summer progresses. However, early cultivars are still susceptible to the disease, so if weather conditions mean that the disease gets going early in the summer they could still be affected

- Gardeners are able to access forecasts of when blight will be active in their region, check if there have been previous instances of favourable weather for the disease, or see if there have been confirmed cases - visit the BlightSpy website, developed for professional growers but providing useful information for gardeners

- Picking off leaves or leaflets when just a few are affected may slow down the progress of the disease very slightly, but will not eradicate the problem

- When infection levels reach about 25 percent of leaves affected or lesions appear on stems cut off the foliage (haulm), severing the stalks near soil level and raking up debris. When the skin on tubers has hardened, after about two weeks, the tubers can be dug up. To prevent slug damage avoid leaving tubers in the soil after this time

- Use the tubers from blighted crops as soon as possible, and avoid storing them if at all possible. Check any stored tubers regularly for decay

- Operate a rotation to reduce the risk of potential infection from soil-borne resting spores (see ‘Biology’ section, below), ideally of at least four years (also avoid growing tomatoes in the soil during this period)

- Destroy all potatoes left in the soil, and any waste from storage, before the following spring

The population of the blight pathogen is ever-changing and recent research has shown that new strains seem to have overcome the resistance previously exhibited by some cultivars. In the past some potato cultivars had shown limited resistance, these included ‘Cara’, ‘Kondor’, ‘Orla’, ‘Markies’ and ‘Valor’, but this is not currently effective. There are, however, still cultivars currently thought to show good resistance to the disease, including Athlete, Alouette, Carolus and the Sarpo cultivars (e.g. Sarpo Axona, Sarpo Mira). These cultivars are not completely immune, so may still develop blight if prolonged favourable conditions for the disease occur, but not to the same extent as susceptible cultivars. Some old favourites are very susceptible, eg ‘Arran Pilot’, ‘King Edward’, ‘Majestic’, ‘Sharpe’s Express’. Visit the British Potato Variety Database for more information. The latest situation with regard to the dominant strains of blight can be found on the Euroblight website.

Chemical control

There are currently no fungicides available for use by gardeners for use against blight.

Biology

The late blight pathogen is a microscopic, fungus-like organism whose spores (sporangia) easily break away from infected foliage and may be wind-blown for long distances. In order for infection to occur prolonged surface wetness (several hours) is required; this is why the disease is so serious in wet summers. The pathogen then spreads rapidly through the plant tissues, killing the cells. Under humid conditions, stalks bearing sporangia grow from freshly killed tissues and the disease can spread rapidly through the crop. Spores produced on the leaves and stems can also be washed down into the soil by heavy rain, and may infect tubers that they come into contact with.

The pathogen overwinters in affected potato tubers left in the ground (and also left by the sides of fields in the case of some commercial crops affected the previous year). Whilst it’s possible that tomato or potato material left in an individual garden could act as a source of the disease for the following year, the great majority of infections in gardens arise from wind-blown sporangia originating from other gardens and allotments, and from commercial potato crops. In the UK, outbreaks may occur from June onwards, usually earliest in the South West.

The presence of new blight strains in the UK means that the pathogen now has the potential to produce resting spores (oospores) in the affected plant tissues. The oospores are released from the rotting tissues to contaminate the soil. These resting spores have yet to be found in the UK, but analysis of the recent variations in blight strains occurring on potato crops in some parts of the UK suggests that they could be being produced. Little is currently known about their survival and their potential as a source of the disease, but investigations are continuing and more information is likely to become available over the next few years. However, because oospores are resilient structures, if they are produced in infected foliage it is quite possible that they will also survive many home garden systems. This is why it is preferable to dispose of waste from blighted crops in other ways. Municipal and commercial composting systems should reach the very high temperatures necessary to kill oospores and other resilient pathogen propagules.

Attacks of blight occurring in late summer can defoliate potato crops, but if the disease arrives when the tubers are already mature, and they are harvested before they become infected, little is lost. However, early attacks can be devastating and, more than 150 years since the Irish potato famine, blight is still the most important disease of potatoes, both for gardeners and commercial growers.