Quick facts

Plants multiply by sexual reproduction or by making clones of themselves

Poor pollination is a common cause of low fruit harvests – luckily there are things we can do to ensure a good crop

Seeds are living organisms with a limited lifespan – for successful germination, they must be kept and sown in suitable conditions

Reproduction by seed

Most flowering plants produce seed as their main method of reproduction. A seed contains a miniature plant, different from its parents, that can be dispersed to colonise a new habitat.

There are three main steps in this process:

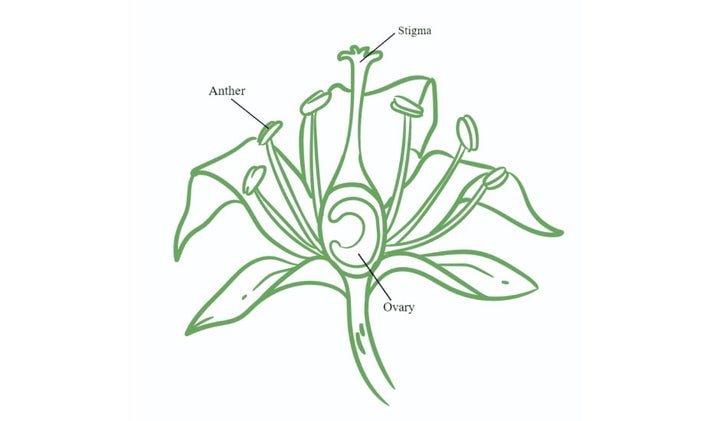

- Pollination – this happens when a male pollen grain, released from a male anther, meets the female part of a flower, the stigma. The grain germinates and travels down from the stigma into the plant’s ovary, within or just behind the flower.

- is the next stage – when the nucleus of the pollen and the ovary’s egg fuse to become an embryo.

- Seed formation – as the embryo develops, from the parent plant build up the seed’s food reserves to aid its survival and early growth. It then loses water, the seed coat hardens for protection, and it becomes ripe and ready for dispersal.

Flowers typically contain both male and female parts – in which case they’re known as ‘entire’.

But some plants produce two different kinds of flower – one with only female parts and another with only male parts. These single-sex flowers may be produced either both on the same plant or on entirely different plants:

On the same plant (monoecious) – hazel (Corylus) is a typical example, bearing tiny female flowers that you may not even notice as well as more showy male catkins. It’s the fertilised female flowers, not the catkins, that develop into hazelnuts.

On different plants (dioecious) – some plants, like skimmia, have separate male and female plants that each produce flowers of only one sex. Take care to buy female plants if you want berries, but bear in mind there must also be a male plant nearby to ensure pollination.

Did you know?

Cultivar names are often misleading when it comes to the sex of a dioecious plant. Hollies (Ilex) are a good example – ‘Golden King’ is a female form and ‘Silver Queen’ is male. If you want one that bears berries, check the plant label carefully before buying to make sure you have a female plant.

Successful pollination

Plants can be either self-fertile or require cross- :

- Self-fertilisation happens when pollen is transferred between flowers on the same plant or even within a single flower. It offers the advantage that only one plant is needed for successful seed production. Sweet peas, beans and tomatoes are common self-fertilising plants.

- Cross-fertilisation happens when pollen is transferred between flowers on two separate plants of the same species. This ensures variation in the resulting offspring, which may provide advantages. Salvias and foxgloves (Digitalis) are examples of plants that are adapted for cross-fertilisation, requiring two compatible plants to be grown in close proximity to produce seed.

Pollen usually travels by two main mechanisms – insects or wind:

- Insect-pollinated plants need to attract suitable pollinators, such as bees, to their flowers. They do this by signals such as scent and colour and by rewards such as nectar. Different insects prefer different types of flowers – while night-flying moths are attracted to white, richly scented blooms, bumblebees prefer brightly coloured flowers. See our guide to insect pollinators.

- Wind-pollinated plants, such as grasses, produce light pollen that can be transported on a breeze. Reaching its destination is chancy, so these plants produce a lot of pollen as an insurance. Wind-pollinated plants don’t need colourful or scented flowers that appeal to insects, just functional ones, so they are often quite inconspicuous.

It’s useful to know which pollination and fertilisation method your plants use, if you want to ensure they produce good crops of fruits, berries or seeds.

Solving pollination problems

Pollination doesn’t always happen smoothly, in which case seeds may not develop and, more importantly for us, fruiting may be poor. There can be many reasons for this, including:

- Too few pollinating insects – it can be too cold for insects to fly and visit flowers that open in early spring, and growing in a greenhouse stops pollinators reaching tender crops. Hand-pollination, using a small brush, overcomes this, guaranteeing pollen is transferred.

- Lack of a suitable ‘pollination partner’ – plants that require cross-pollination (pollen from a different plant) need a compatible ‘pollination partner’ nearby – a similar plant that flowers at a similar time. When choosing cultivars, select them from the same or an adjacent ‘pollination group’ to ensure compatibility and an abundant harvest. See our guides to choosing cultivars of apples, pears and stone fruits.

- Sterile flowers – many plants with don’t have sexual organs, as they have been been modified into extra petals. Such plants can’t act as pollinators for others growing nearby and can’t produce seeds. Take or divide these plants if you want more, and be sure to include plenty of single-flowered, pollinator-friendly plants in your borders too.

- Cold temperatures – pollination triggers production and initiates fruit development. This can be interrupted by cold temperatures, resulting in fewer fruits forming. Cover the blossom of late spring-flowering fruit trees with if low temperatures are forecast, removing it during the day to allow access for pollinators.

- Dry conditions – seed development takes lots of energy, so during a prolonged dry spell plants may flower or crop poorly, prioritising survival above all else. Mulching around the base of fruit trees in late winter helps reduce water loss from the soil, meaning more is available for roots to drink. If you grow fruit trees in containers, pay close attention to watering throughout and straight after the flowering period.

Seed germination

Seeds are living things, containing an embryo – a small immature plant. They develop and ripen on a plant and are scattered, carried or blown to the ground to establish a new generation elsewhere.

starts with the seed coat absorbing water, expanding and splitting. This allows oxygen and water into the seed so its food reserves can be broken down and used by the embryo for growth. The first root (called the radicle) pushes into the soil to anchor the new plant in place and start absorbing water and nutrients. The first shoot (called the plumule) then grows upwards, out of the soil, and its leaves unfurl and start photosynthesising.

If you want to collect seeds from your plants to sow yourself, wait until they are ripe and ready to fall. are in a state, waiting for the environmental conditions, such as daylength and temperature, to become suitable for germination. They’ve evolved their timing to survive the weather patterns in their habitat, so the resulting young plants are more likely to survive.

Most plants suited to our climate will germinate readily in spring when the soil is moist and warm, light levels are good and temperatures are usually on a steady rise. In the UK, April is the prime seed-sowing month.

However, breaking isn’t always straightforward:

Seeds have a limited lifespan – their viability – as they respire and slowly use up their stored food reserves while dormant. Bulky seeds, like peas and beans, contain more food reserves, so often have a longer lifespan than light, fine seeds like carrots. If you store seeds at home, put them somewhere cool and dark to slow down respiration and label them with the date they were collected.

Some seeds have a very hard seed coat that hinders germination. Sweet peas, for example, can benefit from being soaked in water for a few hours before sowing to soften the seed coat, or you can scratch or nick it so water can get in and start the process. Some seed coats even contain chemicals that inhibit germination, and these must be broken down in the soil before it can begin.

The seeds of many trees need exposure to particular periods of hot and cold weather to germinate, which can be difficult to achieve when we sow them ourselves. Seeds of the handkerchief tree (Davidia involucrata), for example, are doubly dormant and won’t germinate naturally until the second spring after sowing. If you want to grow trees from seed, you can speed up the process by stratifying (pre-treating) the seeds, providing periods of warmth (in an airing cupboard) and cold (in a fridge) before sowing.

Asexual reproduction

Unlike humans, plants can make version of themselves – replicas – to help them colonise habitats they are thriving in. New plants produced by cloning are identical to the parent plant, which means you can be sure of what you’re getting – the new plant will stay ‘true to type’, with no variations.

Three common ways this can happen naturally are:

- dividing to form new small bulbs, called offsets – this helps bulbs such as daffodils to spread and form large clumps. The offset bulbs may take several years to reach flowering size

- Sending out runners – tiny new plants on long stems – as with strawberries and spider plants (Chlorophytum)

- Low-lying stems rooting into the ground to produce new plants – a process known as layering. This can happen with various shrubs and climbers, from gooseberries to honeysuckle (Lonicera). Plants that layer easily, or send out roots from their leaf joints, such as periwinkle (Vinca), are useful for creating groundcover, but can sometimes spread too readily and become a nuisance

We can also use methods to create new plants ourselves:

- Pin down into the soil the shoot tips of berries or low-lying shoots of various shrubs and climbers. Once a new, well-rooted plant has formed, the stem connecting it to the parent plant can be severed. See our guide to layering

- Dig up and divide dense clumps of bulbs to establish new colonies around your garden. See our guide to propagating bulbs

- Take from suitable shoots, roots or leaves to create copies of your favourite garden and houseplants. Choose a well-patterned shoot if you want to preserve

- Divide established clump-forming to create multiple new plants. See our guide on dividing perennials

Your next steps

Now you know more about how plants multiply, put this into practice to help your plants thrive:

- Attract pollinating insects to your garden by planting single flowers in a variety of shapes and colours. See our guide to choosing plants for pollinators

- Regularly throughout the summer to stop them running to seed and encourage more flowers. See our guide to deadheading plants

- Watch out for late frosts and dry weather in spring if you grow fruit – as they are the most common causes of a poor harvest

- Check the requirements of your seeds before sowing, by consulting a good plant propagation book, or keeping seed packets for reference

- Fill out your borders by propagating plants that are thriving in your garden conditions. Dividing perennials and taking hardwood cuttings are easy methods to try if you’re new to gardening